Breathing … is the essential process that allows life as we know it. It allows us to push our bodies through the rigors of training and racing. It is well known that the diaphragm is the primary muscle for respiration. It drives the process of gas exchange supplying much needed oxygen to hard working muscles and removing carbon dioxide. But incorrect breathing patterns not only make us less efficient at moving air in and out, it can directly contribute to problematic muscle tightness and over activity, paving the way for injury.

Breathing … is the essential process that allows life as we know it. It allows us to push our bodies through the rigors of training and racing. It is well known that the diaphragm is the primary muscle for respiration. It drives the process of gas exchange supplying much needed oxygen to hard working muscles and removing carbon dioxide. But incorrect breathing patterns not only make us less efficient at moving air in and out, it can directly contribute to problematic muscle tightness and over activity, paving the way for injury.

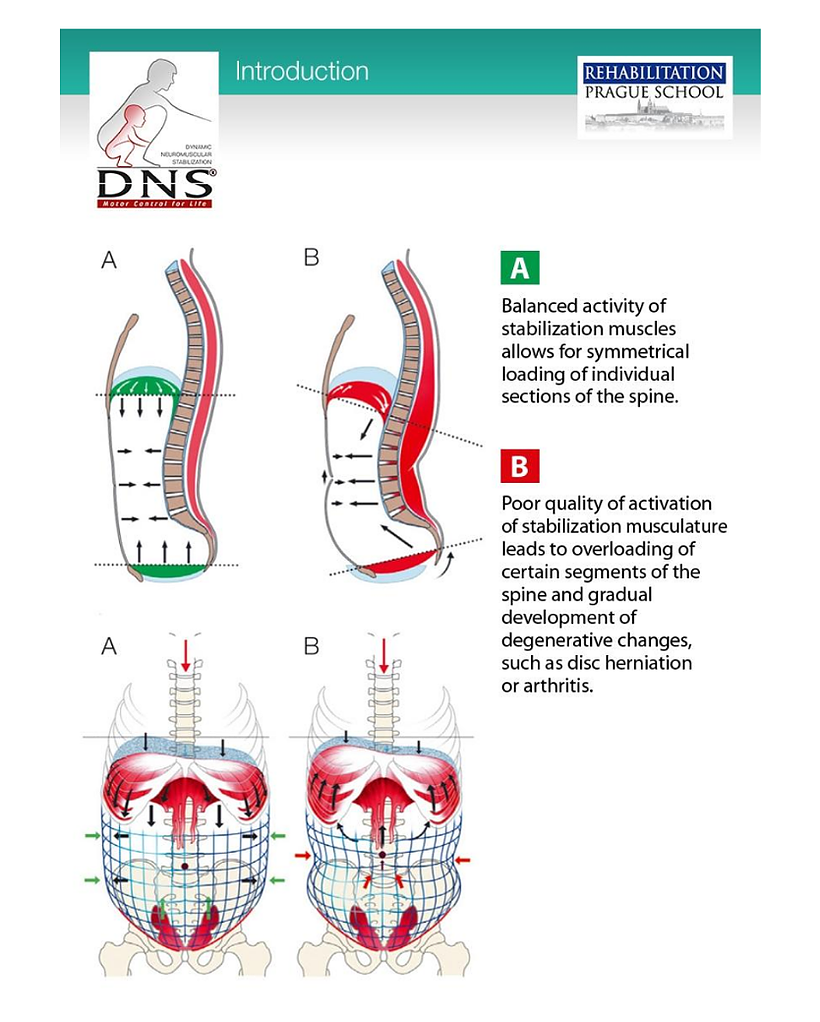

Increasingly researchers have been able to clearly demonstrate the pivotal role the diaphragm plays in correctly maintaining core stability via control of intra-abdominal pressure. This intra-abdominal pressure can be likened to a cylinder whereby the diaphragm forms the lid, the muscles of the abdominal wall form the front and the sides, small muscles of the spine form the back and the muscles of the pelvic floor form its base. It is only through correctly activated and coordinated interplay of all the muscles involved in this cylinder do we get true core stability. This correctly activated cylinder of stability provides a strong, stable (but dynamic) connection from our pelvis to our rib cage. This correctly supports and aligns the spine, minimising stress there. And in turn, this provides a strong and stable platform for our arms and legs to move from to propel us through our chosen sport. Regardless of the sport the goal for all performance is easy relaxed movement with minimal overflow of unwanted tension.

So in the absence of a correctly activated cylinder providing this stable base, muscles that should have dedicated roles in positioning and powering the movement of our arms and legs are then faced with the dual task of attempting to help to provide assistance in stabilizing the cylinder as well as doing their own job. It is this dual tasking that leads to a lot of the problematic tightness we see.

In most sports there are a lot of repetitive movement patterns and positions. Traditionally, these have been blamed for the classic patterns of tightness seen in these athletes. However applying this correct understanding of dynamic stabilisation patterns, these tightness problems can be very much minimised, thereby reducing the likelihood of injury, improving ranges of motion and increasing performance.

Ordinarily the correct pattern of breathing and stabilisation are established early in childhood as part of our musculoskeletal development. However through shortcoming in this development as children or later as a result of injury and bad habits we can lose the ability to correctly activate these key stabilising muscles. Many of the positions and exercises we use to correct failures in the system are based on the positions that should occur automatically in early childhood development.

Try It At Home

You can get a reasonable indication of where you are at with diaphragm activation by following these easy steps:

- Lie on your back and place one hand on the top of your chest and the other on your belly.

- Take a slow deep breath in. Which hand moves first? And which hand moves the most?

- Breathe out.

- Take another slow deep breath in. What moves first? Your diaphragm or your rib cage?

DIME Performance Athlete Logan Kramer performing an integrated diaphragm activation exercise before his strength session.

Ideally your breath should fill from the bases of your rib cage first, feeling like it spreads into the front, sides and rear of your of your abdomen.

Only toward the later stages of a full breath should the upper parts of your rib cage move. If this is not the case simply practicing the correct pattern as described will begin to improve your diaphragm’s role as both a key component of your core stabilisers and also as the primary muscle of respiration. Initially this is best practiced in positions with very little postural load such as lying on your back. As it becomes easier to perform and more automatic you should progress to trying maintaining it in different positions and activities.

About the Authors:

Hudson and Leia Graham are Brisbane based physiotherapists with over 20 years combined experience in musculoskeletal and sports treatment. Both have undertaken postgraduate training with Pavel Kolar and the famed Prague School of Rehabilitation in the methods of Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization. If you would like more information about what you have read here or would like to book an appointment please email us on: body.control@bigpond.com