A muscle cramp is a sudden, involuntary, painful contraction of a muscle [1, 2]. As an athlete, I’m sure we’ve all experienced this phenomenon typically in our lower limb area. Muscle cramps are the most common conditions that require medical attention during or immediately after sporting events [2]. Particularly prevalent in endurance sports such as triathlon and ultra-endurance races. Muscle cramps that occur during exercise are labelled as Exercise Associated Muscle Cramps (EAMC). Although, EAMC are common in athletes, the cause is unknown and controversial [3]. First reports of muscle cramping were noted over 100 years ago in miners working in hot, humid conditions [1-3]. These reports noted that cramp only occurred in the heat and were accompanied by profuse sweating. However, these reports are observational and provide little scientific backing [2]. Due to reports of muscle cramp only developing in hot, humid conditions, “heat cramps” is a commonly used term still today. This is despite the fact that EAMC is known to occur in individuals exercising in moderate to extremely cold temperatures as well as not being related to increasing core temperature [2]. Furthermore, passive heating does not cause EAMC and passive cooling doesn’t relieve muscle cramps.

Anecdotally, many believe cramping comes from muscles being too “tight” which could be relieved by something like a rapid tension relief gun. However, this is likely not the case.

This evidence lead to what is now commonly believed as the predominant cause of muscle cramps. The “electrolyte depletion” and “dehydration” hypotheses [1-3].

Electrolyte Depletion and Dehydration Theories

These theories state: “that because the body does not store enough water for exercise and athletes do not ingest enough water to replace the amounts they lose during exercise, EAMC are the result of fluid and electrolyte depletion.” This decrease of space puts pressure on select nerve endings resulting in muscle cramp [3]. Hence the idea of hot and humid conditions causing cramp due to the extra fluid loss. However, studies have shown that blood electrolyte concentrations in the cramp group was not significantly different to the non-cramping group at the time of muscle cramp. Furthermore, once recovered from cramp, no changes were observed in blood electrolyte concentrations indicating that recovery from cramp is not associated with electrolyte concentration [2].

These theories state: “that because the body does not store enough water for exercise and athletes do not ingest enough water to replace the amounts they lose during exercise, EAMC are the result of fluid and electrolyte depletion.” This decrease of space puts pressure on select nerve endings resulting in muscle cramp [3]. Hence the idea of hot and humid conditions causing cramp due to the extra fluid loss. However, studies have shown that blood electrolyte concentrations in the cramp group was not significantly different to the non-cramping group at the time of muscle cramp. Furthermore, once recovered from cramp, no changes were observed in blood electrolyte concentrations indicating that recovery from cramp is not associated with electrolyte concentration [2].

Due to blood electrolyte concentrations being similar between crampers and non-crampers, proponents of this theory have suggested it is “salty sweating” which causes EAMC due to the increased sodium in the sweat [2]. A large loss of sodium can only occur with a large loss of fluid meaning athletes would be severely dehydrated. There is no research on sweat sodium concentrations of individuals during EAMC, only during exercise in athletes with a self reported past history of EAMC. These athletes were reported to have “high” sweat sodium concentrations which were linked to EAMC. However, athletes with no past history of cramping have consistently higher or the same sweat sodium concentrations as the reported “salty sweaters” indicating these athletes have sweat sodium concentrations from normal to low [2].

Overall, there is no suitable physiological explanation for the electrolye depletion theory. The biggest fallacy is that a loss of electrolytes is a global occurrence in the body but exercise associated muscle cramp is always a localised phenomenon [2].

If electrolyte loss were really the cause of cramp, wouldn’t you cramp everywhere or at least in multiple areas? And furthermore, shouldn’t replacing electrolytes then relieve muscle cramp?

It has been shown that ingestion of pickle juice relieved cramp but not because of changes in electrolyte concentrations in the body [4]. In addition, this theory doesn’t explain why interventions like rest and passive stretching are proven to be effective [2, 3].

Sports drinks may not be the answer to your cramp.

The dehydration theory is linked to the electrolyte depletion theory. Currently, there is not a single published scientific study showing that athletes with acute EAMC are more dehydrated than control athletes. In fact, 4 studies show that cramping athletes at the time of muscle cramp are not more dehydrated than non-cramping athletes [2]. Furthermore, athletes who develop cramp often ingest similar volumes of fluid during exercise compared to non-cramping athletes [3]. If EAMC were due to dehydration, then fluid replacement would be the simple treatment. However, when carbohydrate-electrolyte solution were ingested at a rate to match sweat loss, 69% of athletes still suffered from muscle cramps [3].

Neuromuscular Theory

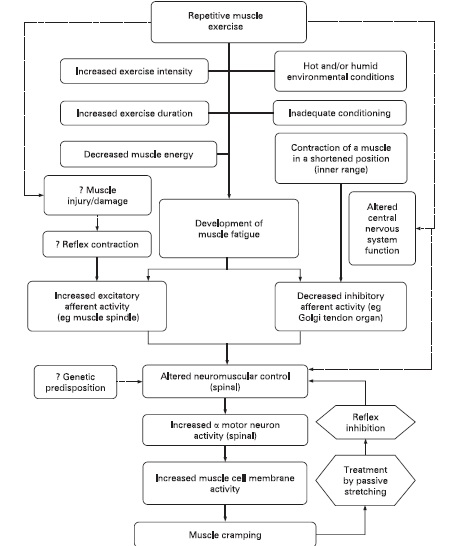

“Altered neuromuscular control” as a result of muscle fatigue is how the neuromuscular theory started in regards to EAMC [2]. It is proposed that muscle overload and neuromuscular fatigue cause an imbalance between the muscle spindle (increased excitatory impulses) and the Golgi tendon organ (decreased inhibitory impulses) [1-3]. This increased excitation (from the spinal level) with decrease in inhibitory feedback (from the tendon) results in an increase in alpha neuron discharge to the muscle fibers, in turn producing the muscle cramp [3]. Cramp tends to occur when the muscle is contracting in an already shortened position because the tension of the tendon (therefore the inhibitory Golgi tendon organ) would be less [2]. Muscle fatigue may play a role in this as in animal studies, muscle fatigue has been shown to increase excitation of the muscle spindle and decrease the inhibitory effect of the Golgi tendon organ [2]. Furthermore, EMG activity is increased in the cramping muscle at rest in athletes who suffer from cramp compared to non-crampers indicating increased neuromuscular excitability.

Practical Treatment of Exercise Associated Muscle Cramps

Passive Stretching: Passive stretching increases tension in the muscles tendon and therefore increases the inhibitory activity of the Golgi tendon organ. So if you start to feel the first signs of cramp or start cramping, static stretching is your first point of call. Is there a way we could prevent cramp from happening?

Pickle Juice (Mouth/Throat Reflex): This idea comes from the fact that certain electrolyte solutions relieve cramp while seeing no changes in electrolyte concentrations in the body. The most notable is pickle juice. A paper by Miller et al. [4] showed pickle juice to relieve cramp 45% faster than when no fluid was consumed. The authors speculate that the pickle juice triggered a reflex in the mouth/throat region which acts to reduce the alpha motor neuron activity in cramping muscles. The primary ingredient in pickle juice (vinegar) has been shown to elicit mouth/throat reflexes [4]. Miller et al. [4] theorise that pickle juice may trigger an inhibitory stimulus and this stimulus may override the increased excitatory impulses from the cramping muscle. Pickle juice or vinegar may be best taken pre sporting event as an “insurance” against cramp. Then at first signs of cramp, a small ingestion of vinegar may help relieve the symptoms. In the research, 1ml/kg of pickle juice was ingested. However, if you are using straight vinegar, you can use less for the same effect.

The multifactorial nature of muscle cramp [2].

Conclusion

The electrolyte-dehydration hypothesis has little evidence backing its case and mainly comes from anecdotal sources. The neuromuscular control theory has greater evidence backing it off human and animal research. Based on the research, the electrolyte-dehydration theory does not explain why the above treatments work. EAMC is likely multi factorial where factors such as conditioning, fatigue and duration of exercise may play a role. The diagram above shows a good flow chart of this idea.

Since vinegar produces a mouth/throat reflex, maybe it’s possible to induce this reflex with other acidic liquids or foods? Further research needs to be done in this area but I’m going to play around with some of my own concoctions to see if we can alleviate cramp in our professional rugby players. If you have any success with any of the above methods or your own, send us a message!