Ice baths, aka Cold Water Immersion (CWI) has been a staple recovery protocol among athletes of many different sports due to the low cost and relative ease of implementation. However, the current literature is conflicting in regards to the physical, physiological and mental benefits. According to Schimpchen et al., [1] previous literature suggests that athletes involved in sports that require neuromuscular coordination and muscular power may potentially benefit the most from CWI. Hence, the authors have just published a new paper investigating the effects of CWI in elite power athletes.

Max Lang, one of the German Weightlifters

Who Were The Athletes

7 Male members of the German National Olympic Weightlifting team from bodyweight classes ranging from 69 – 105kg. All 7 athletes were preparing for the World Championships in 3 months’ time so were well into their training.

What Were The Procedures

A randomised cross over design was used for this study. Meaning all athletes underwent both conditions and the order of conditions were randomised. The two conditions were CWI immediately after each session or a control condition. CWI protocol consisted of one single 10min ice bath (12◦-15◦C) seated and immersed up to neck height. The control group consisted of 10min passive recover in the same position. Each “phase” or condition lasted for four days where athletes trained twice on Monday, once on Tuesday and twice on Wednesday totalling 5 sessions for 3 days.

Testing was performed on the first and last day of both phases. The performance test consisted of a snatch pull at 85% and 90% of each athlete’s individual snatch target weight for the World Championships. Maximal bar velocity (Vmax) during the pull was recorded as the performance variable which has been shown to be a relevant performance indicator in weightlifting. Blood tests were also taken for measures of creatine kinase (CK), cortisol and testosterone. NOTE: creatine kinase is a marker of training stress influenced by fitness level, duration, intensity and mode of exercise. Not to be mistaken with creatine found in red meats and the supplement store. As well as all this, subjective ratings were obtained through questionnaires that were filled out every morning. These questions described physical, emotional, mental and overall aspects of recovery and stress.

Not German Anthony Taylor lifting for New Zealand

What Did The Authors Find

5 training sessions in 3 days induced a strong subjective sense of fatigue in the athletes in BOTH conditions. Questionnaires showed a significant decline in overall recovery and higher rating of overall stress. Blood tests revealed a significant increase of CK and lower values of cortisol.

Athlete’s subjective feeling of overall recovery was very likely positively influenced by CWI. However, overall performance capabilities were not enhanced during the CWI condition.

According to the authors, CWI has previously been shown to significantly improve squat jump performance in non-elite, resistance trained athletes after a DOMS inducing strength training session [2]. This shows CWI could potentially be a good recovery method for power dependent movements [1]. The reason performance may not have improved overall in the German weightlifters, is that the snatch pull is a very strength based movement due to the external load. The improved subjective feeling of overall recovery may have come down to the placebo effect (which is never a bad thing when dealing with athletes). The authors suggest to stress the importance of recovery to athletes and therefore potentially increasing the athletes’ responsiveness to the recovery protocol. Overall, performance was not negatively affected during the CWI condition over 3 days of training.

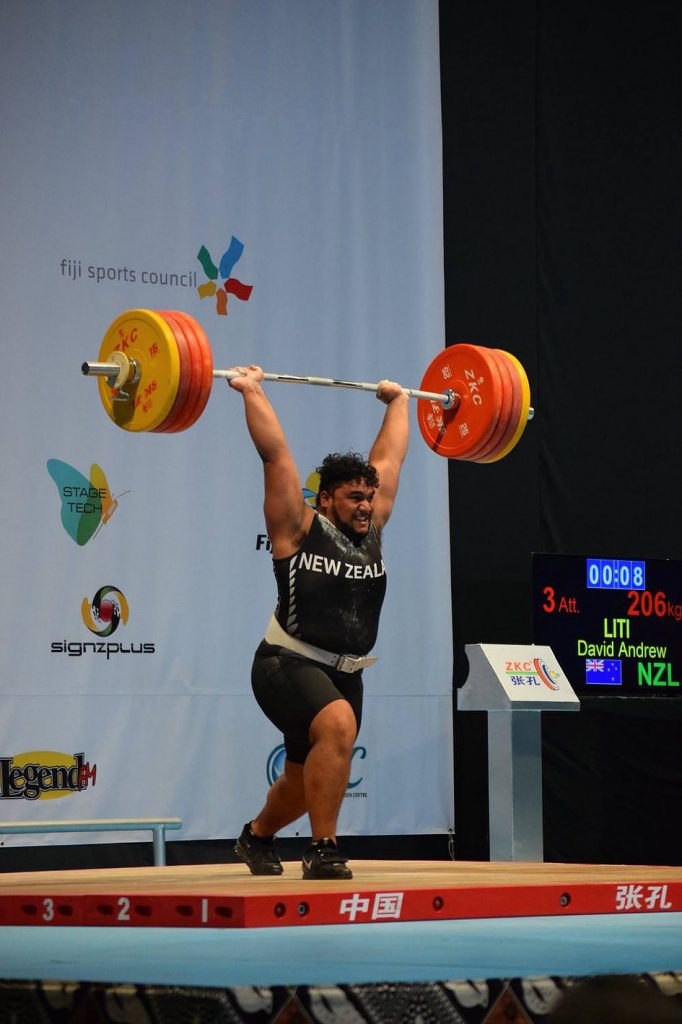

Not German David Liti lifting for New Zealand

A unique perspective of this paper was the authors looked at individual responses to the CWI. One athlete improved performance in both 85% and 90% snatch pull tests in the CWI condition but saw a decline in performance for both tests during the control condition. In addition, questionnaires revealed an improved feeling of overall recovery and less overall stress for the CWI condition vs. the control. In contrast, two athletes performed consistently worse in the 85% and 90% snatch pull tests during the CWI condition and better or the same during the control condition. Questionnaires for these athletes’ showed no or only slight differences in feeling of recovery.

Practical Applications

The findings of this paper bring to light the importance of individual responses to recovery and performance. For the competitive athlete, CWI may be helpful in phases immediately prior to competition. However, this depends how you respond to using ice baths as a recovery protocol.

If you subjectively feel fresher and less sore, then the ice bath is the perfect recovery tool you leading into a competition. If it increases your stress thinking about jumping in an ice bath and you don’t feel like it is helping you, then other recovery options may be more beneficial to you.

It is important to note that using ice baths during heavy training blocks (e.g. no regular games or no regular competitions) is not recommended and can be detrimental to your training progress. Frohlich et al. [3] showed the effects of regular CWI on strength training adaptations over a 5 week training cycle in sport students. They found muscular strength reduced by 1-2% for the CWI condition vs. control condition. Further research has also shown long term CWI can blunt adaptations to strength training, reducing the long term training gains in strength and hypertrophy [4]. However, more recent research is pointing towards the trend of ice baths enhancing training quality and therefore, training adaptations.

I am a firm believer in not ‘forcing’ recovery as the body needs stress in order to adapt to the stimulus being provided. Recovery is multi-faceted and in my opinion, shouldn’t be viewed as a single protocol. Rather it is a combination of many different variables that come together that come from the coach as well as the athlete himself. During a competitive season, the most important part of the week is competition day not the training adaptations themselves. Hence risking a potentially small reduction in strength is worth the price IF athletes feel better recovered when it comes time to compete.